launched August 3, 2013

to Hill Beachey Day Proposed

to research question number 1

to research question number 2

to research question number 3

to research question number 4

to research question number 5

to research question number 6

to research question number 7

to research question number 8

Ron Roizen

Wallace

The one

hundred

fiftieth anniversary of October 24, 1863 falls on October 24,

2013.

I suggest we celebrate it, make it a public

holiday in Idaho. I propose it be named “Hill

Beachey Day.” Idaho’s legislature could declare

it an official state holiday, to be celebrated annually, in next year’s

legislative

session.

The one

hundred

fiftieth anniversary of October 24, 1863 falls on October 24,

2013.

I suggest we celebrate it, make it a public

holiday in Idaho. I propose it be named “Hill

Beachey Day.” Idaho’s legislature could declare

it an official state holiday, to be celebrated annually, in next year’s

legislative

session.

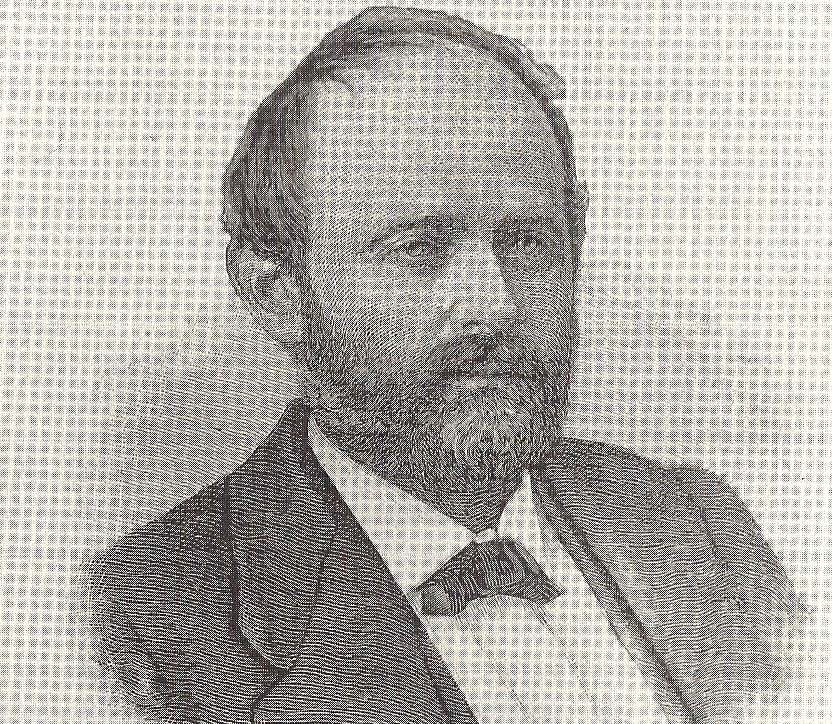

This was the day, in 1863, when Hill Beachey set out from Lewiston to track down and return to justice three men named James Romaine, David Renton, and George Christopher Lower. They, he strongly suspected, had murdered Lloyd Magruder, Charles Allen, William Phillips, and the brothers Horace and Robert Chalmers, which crime has become collectively known as the “Magruder murders.” Not much about murders isn’t disputed or rendered differently by different historians and writers. Yet, the story’s main elements are clear enough. It was one of the most ghastly and notorious crimes in the history of the American West. It also tested for the first time the new justice system of the new Idaho Territory.

Lloyd Magruder took a pack train of mules loaded with mining supplies and other goods from Lewiston to the Alder Gulch mining camps in the summer of 1863. He set up shop in Virginia City, where he soon sold out his wares. In early October, he started back toward Lewiston, now with unloaded mules but carrying considerable gold dust from his successful trading venture. En route, Magruder and his crew were brutally and cold-bloodedly killed by the three men (and perhaps a fourth), who were ostensibly traveling with the company as helpers.

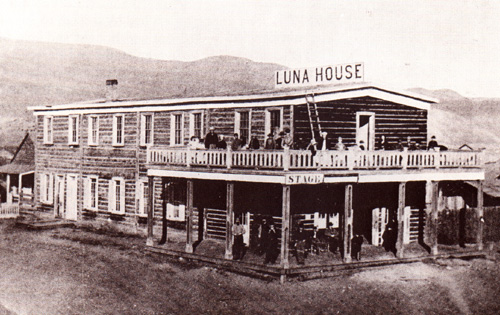

The

killers then

made their way to Lewiston and booked passage on the stagecoach to

Walla Walla,

going from there to San Francisco. How,

exactly, they aroused suspicions as they passed through Lewiston is a

matter of

considerable debate. Some accounts,

going back to Nathaniel Langford’s semi-fictionalized account in his

Vigilante Days and Ways (1890),

emphasized the importance of a prophetic dream Hill Beachey, Magruder’s

friend

and owner-manager of the Luna House hotel in Lewiston, is supposed to

have had,

in which Beachey foresaw Magruder’s murder by an axe-wielding Chris

Lower. But Julia Conway Welch, whose book, The Magruder Murders:

Coping with Violence

on the Idaho Frontier (1991), offers arguably the most scholarly and

sober

rendering of this history, makes a strong case against the dream and

its role,

suggesting Langford introduced it merely for dramatic effect. One

nearly contemporary newspaper account

reported that suspicions gathered around the fact that the suspects

abandoned fine

horses and expensive gear in Lewiston without making any provision for

their

sale. Perhaps there is even something to

historian Hubert Howe Bancroft’s suggestion that Beachey saw “the mark

of Cain,

which seldom fails to be visible” in the suspects. Whatever the

full array of suspicion-exciting

clues may have been, on October 24th Hill Beachey, accompanied and

assisted by Thomas Farrell, headed out of Lewiston to track down and

bring to

justice the suspects.

It’s well to pause, here, and consider some of the remarkable features of Beachey’s fateful decision. He was not a trained lawman or tracker. His absence would be costly. He had at least two businesses to run in Lewiston – a stagecoach line as well as the hotel – and he had other new projects in progress in town as well. He did not know the four suspects names or much about them. He did not know where they were headed or whether they would all travel together or soon split up and go in different directions. His decision obliged him to leave the comforts of home and the warm bed he shared with his wife. He’d be gone for an unknown length of time and at his own expense. Moreover, he could not be one hundred percent certain that his friend Magruder had actually met with foul play. Finally, believing that the men he pursued were coldblooded killers, giving chase would obviously expose him to no little danger and peril. Yet Beachey, despite all of the above, decided to embark all the same.

The suspects had a several-days head start on him. The trail Beachey and Farrell picked up indicated they’d boarded a steamer for San Francisco at Portland. Rather than wait for another steamer’s departure, Beachy headed overland, by stage, to Yreka, California, the first place with telegraph service to San Francisco. There, he wired police chief Martin Burke requesting that the men be detained. Burke, in turn, assigned the case to Isaiah Lees, his department’s crack detective. Lees soon found and arrested the suspects. The suspects made a substantial deposit of gold dust at the San Francisco Mint for conversion to coin. The police’s unearthing of this clue speeded their capture.

But the

apprehended

suspects were not without resources and soon hired a lawyer to fight

their

extradition to Idaho Territory. The

question of whether the police department should surrender the

prisoners to

Beachey was kicked up to the governor’s office in Sacramento.

California’s Governor Leland Stanford

apparently met with Beachey and issued an order for the prisoners’

transfer to

him on November 2nd, 1863. Meantime,

a habeas corpus suit filed on the

prisoners’ behalf was making its way through California’s judicial

system. Among other points, the suspects’ lawyer

argued that the U.S. Constitution made no specific provision for

extradition

from a U.S. state to a U.S. territory.

On November 11th, after a second day of hearing the case,

Justice Edwin B. Crocker announced from the bench that the defendants’

writ was

denied and a written opinion would follow “as soon as

practicable.”

Beachey now took custody of the prisoners

and, from San Francisco, soon boarded the steamer Pacific for Portland.

Below

the mouth of the Williamette River his party transferred to the steamer

Julia.

They were henceforth accompanied by a military guard provided by

General

Alvord at Vancouver. “Steam

had been kept on the Julia for more

than thirty hours, awaiting their arrival,” reported the Portland

Oregonian.

At Walla Walla, Beachey’s party once

again transferred, this time to a stagecoach for the final leg to

Lewiston.

The three alleged killers were tried in Lewiston in January, 1864. A fourth man, Billy Page, pleaded that he took no part in the killings and testified against the other three. Page was spared. Considerable care was taken that the defendants received a fair trial. A contemporary newspaper account noted:

It

might not be inappropriate to say

that this trial, conducted so formally and orderly, will be productive

of much

good in this country. It is the first session of the District Court

ever held

in the Territory, and the first cause tried, and one unparalleled in

brutality

of design and accomplishment ever placed in the records of crime.

The trial’s outcome would also become the first legally sanctioned execution in Idaho Territory, held on March 4th, 1864, the first anniversary of the territory’s creation.

What can mere words add about Beachey’s brave and loyal service to his friend, Lloyd Magruder? Giving chase, as he did -- with so little evidence to go on, so much risk to face, and what must have seemed no great prospect of success – was an action that would become stamped indelibly Idaho Territory’s early history. His ultimate success also marked him as a man who could effectively surmount challenges and bring even the most difficult and trying task to completion. Idaho’s territorial legislature granted Beachey $6,244 “for money expended, and time employed” in the capture and return of the three murderers. This was a tidy sum in 1864, to be sure. Yet, it doesn’t seem quite sufficient somehow. Without his courageous decision, the Magruder murders would have become lodged in Idaho’s history without the closure wrought by justice well served. It elevates Idaho’s historical story to know that the first year of the Territory’s existence witnessed Hill Beachey’s towering act of friendship, loyalty, courage, and commitment to justice.

So,

yeah, I say let’s

create an Hill Beachey Day on Idaho’s calendar, starting October 24,

2013! Keeping his memory alive seems entirely

fitting.