launched August 3, 2013

to Hill Beachey Day Proposed

to research question number 1

to research question number 2

to research question number 3

to research question number 4

to research question number 5

to research question number 6

to research question number 7

to research question number 8

One of

the more dramatic moments in Beachey's story happens when he and his

prisoners arrive back at Lewiston. Hamilton's account, among

others, holds that an angry mob was quite ready

to lynch the alleged murders on the spot (Ladd Hamiton, This Bloody Deed: The Magruder Incident,

1994, pp. 168-175).

Beachey's sober plea

that they should receive a fair trial saved the day.

One of

the more dramatic moments in Beachey's story happens when he and his

prisoners arrive back at Lewiston. Hamilton's account, among

others, holds that an angry mob was quite ready

to lynch the alleged murders on the spot (Ladd Hamiton, This Bloody Deed: The Magruder Incident,

1994, pp. 168-175).

Beachey's sober plea

that they should receive a fair trial saved the day.But. Was there a mob? Did Beachey actually give a quelling speech?

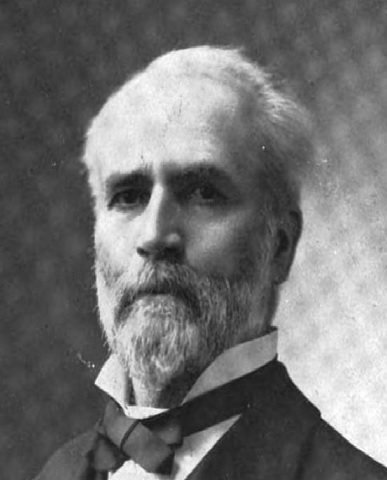

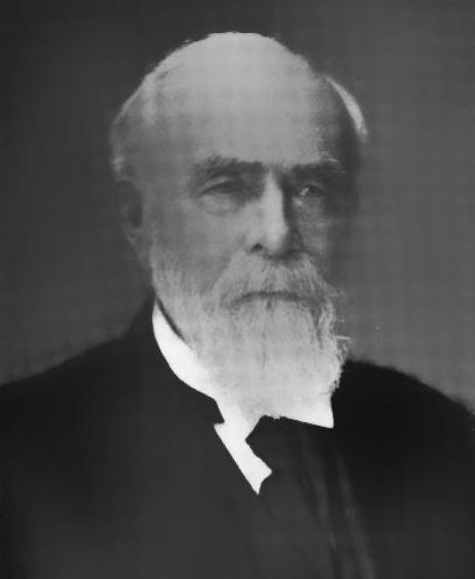

Ladd Hamilton

We have a curious historiographic situation to face in these questions. A contemporary newspaper report, in Lewiston's The Golden Age, will be pitted against authors writing after the fact and, in some cases, with motives that went rather far beyond the pursuit of rigorous historical accuracy.

Hamilton candidly admitted there was a problem with his account. He wrote, in an endnote:

What did Hamilton's "Bibliography" add? Hamilton's commentary began:

Hamilton continued:

Hamilton concluded his argument by drawing attention to another example of inaccuracy in contemporary newspaper accounts, this time quoting The Dalles Journal's Nov 2, 1863 story of the discovery of Magruder's body by a stranger (which story, incidentally, I quoted in my discussion of research question number 4).

Much as I agree with Hamilton that many contemporary newspaper reports were unreliable, his argument regarding The Golden Age's story on Beachey's return is uncompelling.

For one thing, a story about faraway events in the Sacramento Daily Union and one in The Dalles Journal about a stranger's discovery of Magruder's body are a far cry from what Hamilton asserts The Golden Age did. Lewiston's newspaper would have had to deliberately misreport a very newsworthy event in the town's history if a lynch mob actually greeted Beachey's arrival.

Hamilton noted that four other sources -- An Illustrated History of North Idaho, Langford's, Vigilante Days and Ways, Welch's, The Magruder Murders, and Hailey's History of Idaho comported with his account. Yet this element of his argument may be questioned too. Let's carefully examine what each source Hamilton cited had to say about Beachey's arrival in Lewiston.

Welch's book treated the event in only a cursory way. The sum of what she wrote consisted of this: "...he [Beachey] had to talk a crowd of aroused vigilantes out of trying to take the men and hang them on the spot. Fortunately, he was liked and trusted in the town and had long experience with frontier situations" (p. 56). In short, Welch's narrative did not examine Beachy's arrival in detail.

Similarly, the Illustrated History (1903) offered hardly more:

Hailey's (1910) account, however, was a little longer:

They [Beachy and party] were met on the

bank of the river near the town by a large crowd of good citizens who

had

become convinced beyond any doubt that Mr. Beachy had the men that had

committed the murder, so they met them with a rope for each man,

prepared to

make a short job of dealing out justice to them. But Mr. Beachy said,

"No,

gentlemen, I have given my word to the Judge and the Governor of

California and

to Captain Lees, and also to these men, that they shall have a fair

trial by a

court and a jury, and I want to keep my promise." The voice of no

man, save and except Beachy

's, could have caused these people to halt in their determination to

execute

the criminals on the spot. But they all

respected, loved and admired Mr. Beachy for the many noble things he

had done,

and especially for what he had done in bringing these men to the bar of

justice. When Mr. Beachy finished his short

but firm talk, order was restored and the people repaired to their

respective

avocations, satisfied that what Mr. Beachy said was right and they

would not

interfere in any way to obstruct the ends of justice to be dealt out by

the

courts. The men were confined and safely

guarded. (p. 71)

John Hailey

As was

Langford's (1890):

At the mouth of the Columbia, a small steamer with a military escort received the prisoners. They were conveyed immediately to Lewiston. A large assemblage had gathered upon the wharf, intending to conduct the prisoners from the boat to the scaffold. Protected by the military, Beachy succeeded in removing them to his hotel, amid loud cries of " Hang 'em," " String 'em up," by the pursuing crowd. He then appeared in front of the building, and in a brief address informed the infuriated people that one of the conditions on which he obtained the surrender of the men was that they should have a fair trial at law. He had pledged his honor, not only to the prisoners, but to the authorities, that they should only be hanged after conviction by a jury. This pledge he would redeem with his life if necessary. He made it, believing that his fellow-citizens of Lewiston would stand by him. " And now," said he, "as many of you as will do so, will please cross to the opposite side of the street." The movement was unanimous. "

Be gorra ! Mr.

Beachy," exclaimed an Irishman, after he had passed over, "you're the

only mon in the whole congregation that votes against yourself." (p.

344)

It

may be noted that Thomas J. Dimsdale's The Vigilantes of Montana: Or, Popular

Justice in the Rocky Mountains (1866, see p. 112), the earliest

recounting of the story of the Magruder murders, made no mention of an

angry mob at Lewiston greeting Beachey's party's arrival.

Neither, interestingly, did Sheriff Fisk's account, written in

1910. Fisk would have been particularly likely to have

mentioned any unpleasantness at the Lewiston arrival, as he claims the

prisoners were turned over to his custody on arrival. Fisk also

recalled that Beachey and his prisoners arrived

by stage, not boat. He wrote:

In due time Beachy, with his

escort and

prisoners, arrived in the Columbia river, and were transferred to The

Dalles steamer at the mouth of the Williamette without touching at

Portland; thence on to the military port at Walla Walla, and they were

conveyed by stage thence to Lewiston, where the prisoners were turned

over to my custody.

Fisk

then described examining the prisoners and finding a small saw device

concealed in Lowry's hair, with which he had partly sawed through his

chains. It seems unlikely the sheriff

would have failed to mention an angry reception for the prisoners in

Lewiston..

The

key point I would like to stress, however, is that Langford

fictionalized

aspects of his account of the Magruder murders. Welch, herself,

noted this. She wrote: "Because Langford's version used the

methods of

fiction, and because he showed the influence of fiction of his time,

his account has more in common with legend than history" (p.

104). Welch also noted that even unreliable elements of

Langford's

historical account -- elements that were "untrue from internal

evidence" (loc. cit.) -- often became

repeated by in the works of subsequent authors.

All

of which raises the question of where, exactly, the story of the angry

lynch mob and Beachey's quelling speech originated. It is

arguably

quite likely, it seems to me, that Langford's account is the story's

source. And, if so, then the story may be commensurately

downgraded in terms of its likely historical accuracy.

It

comes down to this, then: Notwithstanding an appreciative regard

for Hamilton's work and opinion on the case, it seems more likely --

more plausible -- that Langford fictionalized Beachey's arrival.

The angry mob and Beachey's speech certainly boost his account's

dramatic content. Hailey, in turn, probably borrowed the mob

element from Langford's account -- he (Hailey) gave no sources.

Beyond that, both the Illustrated

History's and Welch's accounts treated the Lewiston mob and

Beachey's return so fleetingly as not to bear much weight.

It may be concluded then that the account

offered in The Golden

Age and the absence of any mention of

the Lewiston mob in Fisk's account relatively gain

historical credence. I'm actually quite sorry to

see the Lewiston mob and Beachey's speech leave this story, if they

must. What's needed now are better sources on Beachey's arrival

in

Lewiston.

Surely, there must be other contemporaneous accounts somewhere.

These must be found

before any final historical judgment can be rendered on this element of

the story.

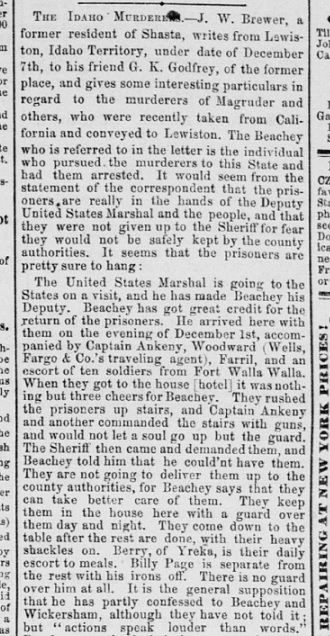

Finding (8/12/2013)

Well, well, well! Now comes

another newspaper source reporting that no lynch mob greeted

Beachey's arrival with his prisoners at Lewiston. The following

clip is drawn from a report appearing in the Sacramento Daily Union for December

25, 1863. It offers valuable details on Beachey's arrival and

tends to confirm the report in The

Golden Age that Ladd Hamilton discounted. It's also worth

noting that this newly unearthed report differs from Fisk's account in

that it says the prisoners were not turned over to his (Fisk's) custody

on arrival. My inference is that Beachey and others may well have

had concerns about the prisoners' safety in Lewiston even if the

party's arrival did not occasion a threatening situation.

This new and independent Sacramento

Daily Union report, by J.W. Brewer, which was apparently

prepared by someone who witnessed the events he writes of, further

erodes the credibility of Hamilton's more dramatic account of Beachey's

arrival.

From the Sacramento Daily Union,

Dec 25, 1863

Finding (8/21/2013)

Thanks to Julia Conway Welch's book (see p. 120 therein), I've picked up another source on the question of Beachey's reception at Lewiston, in Hubert Howe Bancroft's Popular Tribunals (Works, 1887). Bancroft's account cites no sources and thus its historical verity is difficult to assess. Nevertheless, Bancroft's text may be added to our list of historical accounts that make no mention of a lynch mob or a quelling speech on Beachey's part. On the contrary, Bancroft wrote (pp. 662-663):

Send news to ronroizen@frontier.com, along with any pdfs or other copies of the materials.

New materials, whenever they are appropriate, will be published on this page as they arrive.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you!