launched August 3, 2013

to Hill Beachey Day Proposed

to research question number 1

to research question number 2

to research question number 3

to research question number 4

to research question number 5

to research question number 6

to research question number 7

to research question number 8

Research Question Number 7: What enterprises was Beachey obliged to leave behind when he pursued the four suspects?

For

me, the heart and soul of Hill Beachey's story resides in his singular

decision to give chase to the four suspects. This decision was

his towering act

of loyalty, courage, friendship, and sacrifice

For

me, the heart and soul of Hill Beachey's story resides in his singular

decision to give chase to the four suspects. This decision was

his towering act

of loyalty, courage, friendship, and sacrifice Everything else -- the chase itself, the difficulties he encountered in San Francisco and Sacramento, the return of the prisoners to Lewiston, and the preparations for the trial -- represent, in a sense, mere sequelae and consequences of that fateful decision.

Hill Beachey (image borrowed from Steven D. Banting's Historic Firsts of Lewiston, Idaho: Unintended Greatness)

In this installment of I'd like to direct some attention to the responsibilities and enterprises Beachey had to leave behind, put on hold, or delegate to others on account of this decision.

These abandoned activities represented in effect some the sacrifices his decision to give chase imposed on him.

Obviously, he left behind the comforts and relative safety of his home and the warm bed he shared with his wife.

But Beachy was a busy and enterprising man, too, and so he had to leave behind both ongoing enterprises and new enterprises he was trying to launch.

It's important, in order to have a full picture of these sacrifices, to inventory the full scope of Beachey's various business pursuits in October, 1863.

Beachey departed Lewiston on October 23rd or 24th and returned on about December 7th -- an adventure spanning a little more than six weeks in all.

The list of enterprises Beachy left behind is impressive, and may include more elements than those we currently know.

- We know Beachey

and his wife owned and ran the Luna House Hotel.

- He also is said to owned and operated the stagecoach line that the suspects booked passage on.

- Beachy also attempted to

launch Lewiston's first public utilities in 1862-1863. Steven D.

Banting's Historic Firsts of

Lewiston, Idaho: Unintended Greatness (2013, pp. 36-37) tells

us:

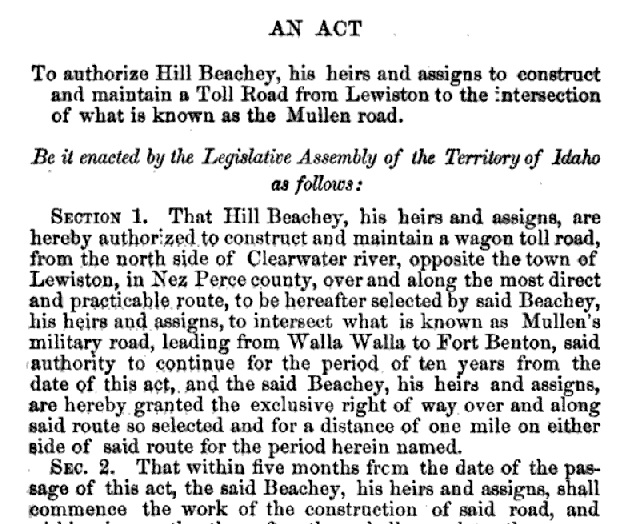

- The Idaho's territorial laws of 1864, first session, include an act, approved on January 22, 1864, authorizing Hill Beachy and his associates "to construct and maintain a wagon toll road" linking Lewiston with the Mullan military road (pp. 662-663). It's safe to assume, of course, given the act's January, 1864 date, that Beachey's planning and preparation for this project was in process in 1863.

He may well have had still more pursuits and preoccupations. For instance, he may well have invested in mining prospects in the region or he may have been a part backer of Magruder's trading venture.

The full array of his enterprises remains to be established. Leaving these enterprises behind was of course one of the sacrifices Beachey had to make to pursue Magruder's killers. Hence, getting a fuller picture of his various pursuits is an important part of the story of his decision.

By the same token, the full story of Beachey's departure from Lewiston in 1864 is not known. Why did he leave? Keith C. Petersen alluded to a competitive rivaly between Beachey's Luna House and Madame Melanie Bonhore LeFrancois' Hotel De France as one of the reasons for his departure (see Petersen, "Five Lives: Idaho in 1863," Idaho Humanities: The Newsletter of the Idaho Humanities Council, Spring, 2013, p. 3). "The De France eclipsed the Luna House," wrote Petersen,

All these questions remain outstanding and worthy of new historical investigation.

Victor Goodwin's 1967 article ("William C. (Hill) Beachey, Nevada - California - Idaho Stagecoach King," Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 10(1):5-46, (Spring) 1967), a valuable new online find for me, focuses on Beachey's post-Lewiston career as a stagecoach businessman. Goodwin wrote (p. 17):

A second new-found source adds the following:

Hill Beachy initially opened a stage

route from Unionville to Silver

City, Idaho, in 1865 for the purpose of transporting supplies, mail,

and passengers from the Humboldt mines to the newly

discovered mines in southwestern Idaho. The

stage route passed through Winnemucca to

Willow Point Station on the Little Humboldt

River, over Paradise Hill to

Cane Springs, and continued north through the Quinn River Valley and on

to Idaho. The duration of the stage line was a short two months

due to stagecoaches and stage stations being burned by Indians.

However, the route was reopened the following

year as Hill Beachy's Railroad Stage Lines for the purpose of

connecting the advancing Central Pacific railhead

with

the mining camps of the Humboldt Range and Idaho. In 1867, a

cutoff

was built from Oreana to Thacker's Station (north of Imlay) and along

the west side of the Bloody Runs connecting with the earlier route at

Cane Springs. This

shortcut bypassed Winnemucca, much to the disgruntlement of its

residents, but in 1868 when the Central

Pacific reached the town, the southern terminus of the Railroad Stage

Lines was moved permanently to Winnemucca.

The route

continued to be used until 1870 at which time Hill Beachy shifted

all

coaches, horses, and stations to his new Elko-Cope-Boise City road

(Goodwin 1966:6-12, Lavelock Sub-basin Section).

This second source is:

The passage I've quoted cited "Goodwin 1966," which citation is:

Michael C. Moore, in his booklet Frontier Lewiston, 1860-1890 (1980), sheds a little more light on Lewiston's declining fortunes after mining enthusiasm turned south to Boise Basin. His contrast between Lewiston in 1862 and 1865 is striking and worth quoting:

Send news to ronroizen@frontier.com, along with any pdfs or other copies of the materials.

New materials, whenever they are appropriate, will be published on this page as they arrive.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you!