|

|

Send comments to ron@roizen.com;

please indicate whether you wish your

comment to be posted to the article.

|

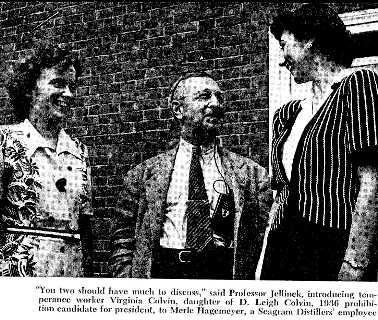

#17 December 26, 2009 E.M. Jellinek's departure from Budapest in 1920, part one by Ron Roizen  Jellinek as pictured in a 1943 Collier's article on the then-newYale Summer School of Alcohol Studies Part 2 of this post available here. He was born in

New York City, the son of Rose Jacobsen and Ervin Marcell Jellinek, and

from high school on, from 1908 until 1930, he traveled the world,

studying at the universities of Berlin, Grenoble, and Leipzig. He

became a biometrician, making statistical analyses of biological

observations, at the Governmnet School for Nervous Children in

Budapest. He studied plant growth in West Africa and directed

research for the United Fruit company [sic] in Honduras. In 1931

he went to the Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts, and eight

years later began heading that hospital's studies into the effects of

alcohol. He became a professor of applied physiology at Yale in

1941.

In 1997

Penny Booth Page threw a little more light on Jellinek's early life in

Budapest. Drawing upon a typescript biographical outline prepared

Jellinek's daughter, Ruth Surry,1 Page conveyed

that after his stint at

the School for Nervous Children Jellinek's life story became cloudy and

mysterious: "According to her [Surry's] notes," wrote Page,2Jellinek next

became involved in currency transactions and then suddenly and

inexplicably left the country. His family heard from him several

years later in Sierra Leone, working under the name Nikita (or Nikipa)

Hartmann (Surry, 1965). He then moved on to the United Fruit

Company in Honduras.

More recently, an American

scholar, Michael Lawrence Miller, who is posted in Budapest, emailed me

the news that a book authored by László Frank published in

Hungary in 1966 included a chapter on Jellinek's currency trading

escapade and his hasty exit from the country.3

At first, Miller and I worked together on a potential coauthored article. With the passage of time however Miller withdrew from the project and generously suggested I should go ahead with preparing an article on my own. Miller kindly sent me his translation of the key elements of Frank's chapter on Jellinek. Frank's account confirmed what Ruth Surry's notes had only hinted, namely that Jellinek had been involved in illegal currency trading and either absconded with a great deal of money or feared the consequences when one of his currency transactions, which involved the use of couriers and cross-border travel, had gone awry. Frank told of events running from mid-May to early June, 1920. Before I summarize Frank's account, it will be well to pause for a moment to note that Frank's narrative provides a single secondary source and a narrative possibly written as many as four decades or more after the events described. Obviously, caution on the reader's part is in order. Frank described a conversation at the apartment of Baroness Somaruga Waldemar on the evening of May 18th, 1920. The baroness maintained a salon, wrote Frank, and "played a central role in Budapest society in the 1920s." A conversation occurred between Jellinek and Gusztav Letay, manager of the Magyar Union Bank. Letay worriedly quizzed Jellinek about dollars he was due to receive. Jellinek fended off his concerns saying the funds would arrive "in about eight days," when Jellinek's courier would arrive. Letay pressed on, now saying that he had not received any funds from Jellinek in two months. Jellinek assured Letay that he would get every last cent of his money. He explained that the delay had resulted from "a little accident that happened at the end of May," which required Jellinek to change couriers in London. According to Frank's account, the two men and two additional parties met the next moring at the Hungaria hotel, where Jellinek maintained a two-room apartment on the 2nd floor for receiving clients. At this meeting, accoring to Frank, Letay wished to commence another currency trade transaction with Jellinek. Letay placed into Jellinek's trust four million crowns belonging to the manager of the Paks bank. Frank continued, Jellinek told the four men waiting that

he had to go to the ministry, and then he was going to Vienna for three

days. Jellinek put some foreign currency into a suitcase and put

diamonds into a large deer-skin pouch. He took a taxi to the Dunapalota

[Danube Palace hotel]….At Dunapalota, he brought the suitcase and

diamond collection to Mr. Atkins (courier), who will get 10% as

commission.

Jellinek’s clients continued

to put pressure on him for the undelivered dollars. On June 1,

according to Frank, Jellinek told Létay that he was going to

Ujszeged to meet with a member of the Entente mission in

Budapest. Létay asked why Jellinek needed to go to

Ujszegeg when his contact was posted in Budapest. Jellinek

explained that his contact had business in Temesvar and would be

traveling through Ujszeged on the Simplon

Express. It was arranged, said Jellinek, that his contact

would give him the dollars at the Ujszeged train station.

The next day, Jellinek and Létay traveled by train to

Szeged. Frank continued:In Szeged, Jellinek and Létay

stayed in neighboring hotel rooms. The Serb border guards

prevented them from crossing the bridge, so Jellinek sought another way

to cross the Tisza River: smuggled in a rowboat.

Létay refused to participate in this adventure. Jellinek

said he would go alone (with the money) and return by the next

morning. By noon the next day, Jellinek hadn’t come back, and

Létay went to the Szeged police. He told the police

captain, Sandor Botka, what happened and asked him to look for

Jellinek’s corpse. Létay remained in Szeged for two

days.

Botka reported that the Hungarian border patrol noticed a boat crossing the river at 10:30 pm on June 2nd. There was a heavy storm, and possibly the two people in the boat drowned. The Serb border patrol also shot at the boat, and it is possible that the passengers were killed. Létay returned to Budapest, but interestingly, he did not report Jellinek’s disappearance to the Budapest police. On June 6, Jellinek’s wife was called to the Budapest police station where she was interrogated by Captain György Mattyasovszky. She told him that Jellinek had disappeared on June 2nd. The police had been investigated Jellinek’s foreign exchange dealings for months, but they had not dared to do anything about them since they knew that people at the highest echelons were involved. Now, after Jellinek’s wife’s testimony, they turned to the prime minister’s office, Jellinek's claimed place of employment, where they learned that Jellinek had been on vacation for half a year. Captain Jenö Marinovich took over the investigation, and he dispatched two detectives (Kristics and Dvorszki) to Szeged. They reported a few days later that no new informantion about the Tisza River crossing had been found. They also confirmed that the Simplon Express stopped in Ujszeged on June 2nd. Due to the presence of an Entente mission, however, there was a tight cordon around the train station. Even if Jellinek did succeed in the river rossing, he couldn’t have gotten close to the train. Jellinek’s trail had disappeared. Many who had put their trust in Jellinek did not worry at first because he had gone abroad before and always come back. Others were afraid to report his absence because their involvement in foreign currency speculation was itself illegal. On June 8, 1920, the government press agency realized that the secret could nott be kept under wraps any longer, and the newspapers were informed. From that date onward the story was daily news. The Magyar Union Bank came under suspicion, but its name was eventually cleared. On June 12, 1920, Sandor Ferenczi submitted the following report: Mr. Morton Jellinek, ministerial

secretary, who has been in treatment with me since January 1917, with

some interruptions, has suffered since childhood from high-grade

psychoneurosis. Symptoms: various forced thoughts, frequent

forced acts, restlessness, impatience and attention deficit.

Unable to concentrate on one place for a long time. At the

current time, unsuitable for any mental work.

Létay came under suspicion. A panic arose and reached its peak in the middle of June. To make matters worse an international boycott of Horthy’s Hungary came into effect on June 20th. The Jellinek family lawyer, Mihaly Vándor, went to Vienna, having heard rumors that Jellinek might have fled there and was perhaps staying at the Hotel Imperial with Atkins, the courier. Finally, on June 28, 1920, an arrest warrant for Jellinek was published in Hungarian and foreign newspapers. He was accused of embezzling 500,000 Hungarian crowns (roughly $3 million in 1920 dollars and ten times that amount in 2009 dollars). E.M. Jellinek – apparently a very rich E.M. Jellinek -- had disappeared into thin air. Part two of this article continues the description of Frank's chapter on Jellinek with Frank's chance encounter with Jellinek in Berlin a decade later. Footnotes: 1 Surry, Ruth, Memo to R. Brinkley Smithers, in: Christopher D. Smithers Foundation Files, Mill Neck, NY. (I thank Penny Booth Page for providing a copy of this document.) 2 Page, Penny Booth, "E.M. Jellinek and the evolution of alcohol studies: a critical essay," Addiction 92:1619-1637, 1997. 3 László Frank, Sélhámosok ü Kalandorok, Budapest: Goldolat, 1966. ©

2009 Ron Roizen

|

Advertisers

Paid advertising provides patronage support for Ranes Report; new advertisers welcome  WildWords  some explorations in the sociology of alcohol

oil paintings and drawings by Maggie Entrekin Roizen |