Contemporary

Drug Problems

26/Winter 1999 [pp. 577-606]

Overlooking Terris: a

speculative

reconsideration of a

curious spot-blindness in the

history of alcohol-control science

BY RON ROIZEN, KAYE MIDDLETON FILLMORE,

AND WILLIAM KERR

The authors argue that the

overlooking or

forgetting

of a beverage-specific element of Milton Terris's classic 1967 paper

linking

per captia alcohol consumption with cirrhosis mortality trends sheds

new

light on the subsequent paradigmatic history of alcohol

epidemiology.

The historical standing and subsequent citation of Terris's paper are

re-examined,

and Terri's reasons for not reminding the alcohol epidemiology

literature

of this aspect of his paper are explored. Aspects of presentation

and content of the 1967 paper are also discussed with respect to the

explanation

of the subsequently lost beverage-specific element of Terris's

article.

The authors suggest that an evolutionarly aspect of the relationship

and

competition between the modern alcoholism and alcohol

controls

paradigms in alcohol epidemiology may offer the key to accounting

for

this historical-forgetting puzzle.

Key phrases: History

of alcohol

epidemiology,

historical forgetting, alcohol and cirrhosis, history of alcohol

science,

paradigmatic strains in alcohol epidemiology.

AUTHOR'S NOTE: This

paper was

supported by a

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) grant (#R01

AA07034) and by an NIAAA Research Scientist Award (#K01 AA00073) to the

second author.

Over the second half of the 20th century,

cirrhosis mortality

in the United States followed a long rising trend and then a long

declining

trend, with the peak rate (14.9 deaths per 100,000 population)

occurring

in 1973. Per capita total alcohol consumption also rose and fell,

but the correspondence between the consumption and cirrhosis mortality

curves was imperfect (see Fig. 1). Moreover, alcohol consumption

peaked in 1980-1981, several  years after

the 1973 peak in cirrhosis mortality, and hence too late for

consumption's

downturn to account for cirrhosis mortality's downturn. Why

cirrhosis

mortality in the U.S. shows this pattern and why cirrhosis mortality

turned

downward in the mid-1970s represent enduring epidemiological

mysteries.

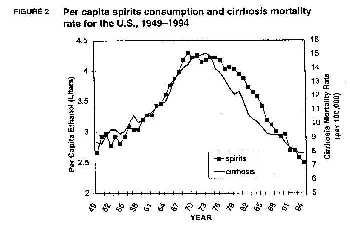

In that connection, we recently reported that the trend-line for per

capita distilledspirits

consumption bears a much closer correspondence to the cirrhosis

mortality

trend than does per capita total alcohol consumption from

1949-1994

(see Fig. 2) (see Roizen et al., 1999). Our article is one of a

handful

in the alcohol studies literature offering explanatory perspectives on

cirrhosis mortality's trend-line in the U.S. (see, e.g., Mann et al.,

1988;

Mann et al., 1991; Gruenewald and Ponicki, 1995; Grant et al.,

1986).

The spirits-cirrhosis relationship does not solve the puzzle of

cirrhosis

mortality's rise and fall, but it may offer a clue as to where that

solution

may ultimately lie (see Roizen et al., 1999, p. 669). years after

the 1973 peak in cirrhosis mortality, and hence too late for

consumption's

downturn to account for cirrhosis mortality's downturn. Why

cirrhosis

mortality in the U.S. shows this pattern and why cirrhosis mortality

turned

downward in the mid-1970s represent enduring epidemiological

mysteries.

In that connection, we recently reported that the trend-line for per

capita distilledspirits

consumption bears a much closer correspondence to the cirrhosis

mortality

trend than does per capita total alcohol consumption from

1949-1994

(see Fig. 2) (see Roizen et al., 1999). Our article is one of a

handful

in the alcohol studies literature offering explanatory perspectives on

cirrhosis mortality's trend-line in the U.S. (see, e.g., Mann et al.,

1988;

Mann et al., 1991; Gruenewald and Ponicki, 1995; Grant et al.,

1986).

The spirits-cirrhosis relationship does not solve the puzzle of

cirrhosis

mortality's rise and fall, but it may offer a clue as to where that

solution

may ultimately lie (see Roizen et al., 1999, p. 669).

Oddly enough, this "clue" has been available

in the alcohol

epidemiology literature for more than 30 years -- though it appears to

have been largely overlooked or forgotten by the alcohol epidemiology

community.

Remarkably, moreover, the clue was suggested in 1967, a half-dozen

years

before disparate consumption and cirrhosis trends began to appear in

U.S.

statistical time-series, and it was suggested in a celebrated

epidemiological

paper: epidemiologist Milton Terris's landmark 1967 article on

alcohol

and cirrhosis mortality. Terris's article included a

beverage-specific

aspect; specifically, Terris (1967) inferred from his trend analysis of

U.S., Canadian, and British data that beer consumption could be

safely disregarded in the aggregate-level relationship between per

capita

alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality. Since wine

consumption

usually contributes only about one-eighth of total annual ethanol

intake

in the U.S., Terris's beer-excluding conclusion implied that per capita

spirits consumption would make the greatest contribution to the

association

between alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality, thus virtually

anticipating

our paper's conclusion (Roizen et al., 1999).

In the present paper, we cast a historical

eye upon the

question of what, if any, significance the dormancy of Terris's

beverage-specific

inference may have with respect to the post-1967 history of alcohol

epidemiology.

Our narrative may be outlined as follows: First, we briefly

re-examine

the historical standing of Terris's 1967 paper and its citation in the

subsequent literature on alcohol's epidemiologic relationship to

cirrhosis

mortality. Next, we examine the question of why Terris himself

did

not alert the alcohol epidemiological community to his

beverage-specific

hypothesis after the appearance of disparate trends in the late 1970s

and

thereafter. Next, we consider whether presentational or

substantive

features of Terris's paper may have accounted for the overlooking of

his

beverage-specific inference. Finally, we examine the ways a

collective

memory lapse regarding the beverage-specific aspect of Terris's 1967

paper

may shed useful light on the relationship and historical development of

two vying paradigms in alcohol studies, the modern alcoholism

paradigm

and the alcohol controls paradigm. We hypothesize that

the

overlooking of the beverage-specific aspect of Terris's 1967 paper may

have derived from a transition from (a) employing an aspect of the alcoholism

paradigm to (b) employing the Ledermann model in order to link

cirrhosis

mortality with a wider orbit of alcohol-related problems.

Terris's 1967 paper's historical

standing and subsequent

citation

Room (1984), Herd (1992), and Katcher

(1993) offer historical

perspectives on the re-emergence of scientific interest in alcohol as a

cirrhogenic factor in the period following publication of Terris's

(1967)

paper. All three note the relative de-emphasis of alcohol

that characterized the prevailing scientific view of cirrhogenesis in

the

immediate post-War period – when the scientific interest in both the alcoholism

paradigm and nutritional and environmental factors in cirrhogenesis

tended to draw attention away from alcohol's cirrhogenic potentials.1

All three also accord a place of honor to Terris's 1967 paper in the

story

of the rebirth of interest in alcohol's role in cirrhosis. Yet

each

of these historical papers positions Terris's article as something of

an

anomaly in its own time -- ahead of its day, greeted with dubiousness

or

scorn, and perhaps thus also deprived of significant contemporary (or

even

lasting) substantive impact on the field.

Room (1984), for example, recounted the

reluctance with

which the paper was received by its initial public health audience (pp.

294-295), noting the retardation of its publication. "Terris'

paper

was omitted from the published proceedings of the session at which it

was

presented," wrote Room (1984, pp. 293-294), "although over half of the

prepared discussion, which was published, focused on Terris'

'provocative

analysis.'" Room's (1984) narrative history next jumped fully 15 years

down the road, to a time by which "a substantial revolution [had]

occurred

in public health approaches to alcohol issues" (p. 294). The

implication

is that the time-leap between the mid-1960s, when Terris's paper was

presented,

and early 1980s, a decade-and-a-half later, saw changes in

epidemiological zeitgeist that

made Terris's paper significantly less anomalous and suspect. Herd's

treatment

of the history of ideas in cirrhosis epidemiology made much the same

leap

(Herd, 1992, see pp. 1119-1120). Hinted in these narrative

handlings

is that Terris's celebrated paper may have occupied a somewhat larger

place

in the historical story of rebirth of attention to alcohol's

role

in cirrhosis epidemiology than in the actual work of practicing

scientists

in the field.

A glance at the bibliographies of well

known reference

volumes suggests the same conclusion. For example, citations of

Terris

are notable for their absences from Bruun et al's (1975) pathbreaking Alcohol

Control Policies in Public Health Perspective, from the main text

of

Moore and Gerstein's Alcohol and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow

of

Prohibition (1981) -- though one of the commissioned papers therein

cites it (Cook, 1981) -- and from Edwards et al.'s Alcohol Policy

and

the Public Good (1994). These well known summary

publications

do not of course constitute the whole of the alcohol epidemiological

literature,

and Terris's paper certainly makes at least occasional "utilitarian"

(i.e.,

as opposed to historical) appearances in a variety of other papers and

book chapters. For example, Reginald Smart (1974), one of the

literature's

earliest and most devoted protagonists of an alcohol-cirrhosis

connection,

cited Terris and Terris alone as authority for the broad assertion that

"Liver cirrhosis deaths have been found to vary directly with per

capita

alcohol consumption in various countries" (Smart 1974, p. 115).

More

often, however, Terris's paper appears to have been cited in the

alcohol-cirrhosis

epidemiologic literature for a specific point rather than as a

general

source for the broader alcohol-cirrhosis relationship per se.

Wolfgang Schmidt (1975, p. 22; 1977a, pp. 29-30; 1977b, p. 11), for

example,

employed Terris's paper to vouchsafe the particular assertion that

cirrhosis's

slow-developing progress at the individual level might

nevertheless

give rise to trend data showing an unlagged decline in cirrhosis

mortality

following declines in per capita alcohol consumption.

Following

Schmidt, Terris's paper may thus have become synonymous with this, or

other,

lesser elements of the epidemiologic case for the alcohol-cirrhosis

connection,

thus obscuring the recollection of the beverage-specific aspect of

Terris's

paper.

Of particular interest is how Terris and

his beverage-specific

recommendation may have been cited or overlooked in literature

specifically

addressing beverage-specific relations between alcohol and

cirrhosis.

This beverage-specific aspect forms only a minor focus in recent

alcohol-cirrhosis

literature -– a status reflected in the recent declaration by the World

Health Organization working group on population levels of alcohol

consumption

that "epidemiological studies so far have not shown convincing evidence

for a differential effect of different types of beverages" regarding

alcohol's

health-related effects (Rehm et al., 1996, p. 277). Nevertheless,

a number of papers, new and old, have examined beverage-specific

alcohol-cirrhosis

relationships. Schmidt and Bronetto's (1962) pre-Terris (1967)

cross-sectional

analysis of U.S. state-level data in 1950 argued that wine consumption

revealed the strongest association with cirrhosis -- perhaps, they

suggested,

because a small subgroup of "winos" made a disproportionate

contribution

to cirrhosis mortality and therefore variation in the size of this

specific

subpopulation state-to-state may account for the association they

reported.

Obviously, Terris could not be cited. More than three decades

later,

Gruenewald and Ponicki (1995) conducted a somewhat more complex

analysis

of U.S. state-level data, this time incorporating a short-term

cross-temporal

dimension as well. They concluded that spirits consumption

evidenced

the strongest association with cirrhosis trends, suggesting (following

Selzer et al., 1977) that "alcohol dependent and alcoholic drinkers

tend

to prefer distilled spirits to beer and wine" (Gruenewald and Ponicki,

1995, p. 635). Terris's paper was cited twice therein -- first,

as

one source for the assertion that past literature had confirmed the

existence

of positive cross-sectional relationships between per capita

consumption

and cirrhosis, and, second, as one source supporting the contention

that

changes in consumption can occasion rapid or non-lagged shifts in

cirrhosis

mortality (cf Schmidt, 1975; 1977a, as noted above). No

mention

of Terris's beverage-specific inference was made and, interestingly,

neither

did Gruenewald and Ponicki (1995) report testing their spirits finding

against U.S. national trend data.

Though it focused chiefly on pancreatitis,

D.N. Schmidt's

(1991) analysis of alcohol consumption and morbidity trends in

Stockholm

County, Sweden offered strong evidence that spirits consumption,

and not beer and wine consumption, consumption was associated with

alcoholic

liver disease trends -- once again relying on the contention that

chronic

alcoholics preferred spirits (D.N. Schmidt, 1991, see pp. 47,

50).

Terris was not cited. Longnecker et al. (1981) found that high spirits

consumption was associated with higher risk of liver cirrhosis

mortality

among white immigrant or first-generation residents of

Pennsylvania.

Terris (1967) was cited but only in the context of a broad introductory

assertion that previous research had linked alcohol consumption with

liver

cirrhosis and other diseases (Longnecker et al., 1981, p.

791).

De Lint and Schmidt (1971) expressed skepticism that any beverage was

more

responsible for cirrhosis, citing cross-national cross-sectional data

to

counter the notion that distilled spirits bore any especially important

causal role. "Clearly," they concluded, "many countries in which

a large proportion of alcohol is consumed in the form of beer and wine

rather than distilled spirits, have high rates of alcoholism" (p.

104).

Terris was not cited. Schmidt (1975) cited Lelbach (1974) as

authority

that the clinical level afforded little support for the influence of

beverage

differences in cirrhogenesis (p. 25), though two older epidemiologic

studies

favoring spirits in cirrhogenesis were also cited (i.e.,

Wallgren,

1960, and Battig, 1964). Schmidt (1975) noted methodological

problems

and the contrary findings of Schmidt and Bronetto (1962) in downplaying

their spirits-emphasizing results. "There exists, then,"

concluded

Schmidt (1975, p. 25), "no valid epidemiological or clinical evidence

which

would suggest that a certain amount of absolute alcohol consumed in one

type of beverage is more likely to produce cirrhosis than when consumed

in another type." As already noted, Terris is cited in this

paper,

but only in relation to the plausibility of consumption changes

resulting

in rapid changes in cirrhosis mortality. Tuyns et al. (1984) said

it all in their paper's title--"Ethanol is Cirrhogenic, Whatever the

Beverage"

-- and did not cite Terris.

Perhaps the most intriguing example of

non-citation of

Terris's beverage-specific recommendation occurred in a useful review

paper

by Jan de Lint (1977) -- offering, as its title suggested, a "Critical

Examination of Data Bearing on the Type of Alcoholic Beverage consumed

in relation to Health and other Effects." Cirrhosis formed only

one

part of de Lint's discussion of beverage-related effects. In de

Lint's

view, many methodological problems lay in the path of drawing a clear

bead

on beverage-specific cirrhogenic potentials (de Lint, 1977,

pp.192-193).

De Lint cited Terris in this connection (among a group of several

references)

for the assertion that cirrhosis mortality's "diagnostic and recording

procedures" vary considerably. De Lint concluded -- quite rightly

-- that at least some of these obstacles could be surmounted by turning

to cross-temporal rather than cross-spacial studies for the production

of more meaningful results, citing Terris (1967) and another paper (de

Lint and Schmidt, 1976) presumably as good examples of this favorable

trend.

De Lint's next sentence read: "These studies [i.e., the two just

cited and perhaps similar efforts as well] thusfar [sic] have not

incriminated

any class of beverage alcohol specifically in the development of

cirrhosis,

but rather have suggested that whatever increases in alcohol

consumption

occur -- whether the results of more beer, wine or distilled spirits

consumption

-- rates of death from this disease increase as well" (de Lint, 1977,

p.

193). With apologies to de Lint, there could hardly be a better

example

of the literature's remarkable spot-blindness to the beverage specific

aspect of Terris's paper -- here dramatically evidenced by the citation

of Terris on behalf of the absence of credible beverage

specific

epidemiologic evidence!

Terris's beverage-specific inference was

not, however,

universally overlooked. "A number of researchers," wrote Smith

and

Burvill (1985), citing Terris (1967) along with Lieber (1982),

Schmidt

and Bronetto (1962), Leavy (1970), and Moeschlin and Righetti (1970),

"have

reported that the consumption of particular alcoholic beverages was

related

to liver cirrhosis mortality, although in his influential review papers

Lelbach (1974, 1976)2 concluded that the type of beverage

was

not important" (p. 42). Similarly, Room (1978 [1970-1971], pp.

279-280),

in a discussion of the well-established link between cirrhosis and the

proportion of heavy drinkers in the population, wrote: "In a whole

series

of studies covering many years, analysts – many of them, as is also

traditional

in the alcohol literature, quite unaware of each others' existence –

have

shown that per capita consumption, particularly of wine and spirits,

tend to vary from year to year in the same population closely with

cirrhosis

deaths" (emphasis added), citing Terris (1967) among the five sources

listed.

Like Schmidt, Room also cited Terris's paper on behalf of the assertion

that short lag-time "‘is consistent with the clinical course of the

disease...'"

(Room, 1978 [1970-1971], p. 280). Our review of this literature

was

by no means exhaustive, but these two sources – Smith and Burvill

(1985)

and Room (1978 [1970-1971] – were the only instances of reference to

Terris's

beverge-specific inference that we have found.

Terris's subsequent nonparticipation

Milton Terris is currently editor of the Journal

of

Public Health Policy. In response to an email query, Terris

kindly

wrote that he had "lost interest in doing further research on the

etiologic

role of alcohol in cirrhosis because [he] was convinced that all of the

data -- the experimental laboratory work, the clinical findings, and

the

epidemiologic data -- supported the hypothesis" (Terris, 1998).

Moreover,

Terris reported that he was unfamiliar with the "U.S. puzzle" that had

overtaken the alcohol-cirrhosis argument in more recent years. In

short, Terris had offered no reminder because he had abandoned his

interest

in the problem; his 1967 paper had been a one-shot effort.

Terris's (1998) email also provided useful

historical

context for his paper and its reception. He wrote that he "was

responsible

for the basic course in epidemiology in the first Graduate Summer

Session

in Epidemiology held in Madison, Wisconsin in 1965." "During my

lectures

on 'Descriptive Epidemiology: Time, Place, Person,'" Terris continued,

I presented the Jolliffe and

Jellinek findings

and their conclusion that there is a significant association of

cirrhosis

mortality with alcohol consumption. One of the students, an

Assistant

or Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Miami School of

Medicine, suggested an alternative explanation, namely, that the

post-World

War II increase in cirrhosis mortality was the result of the increased

use of blood and plasma which caused hepatitis and therefore cirrhosis.

When I got back to New York City, I decided to look into this further,

and I spent a good deal of time at the New York Public Library to

obtain

the alcohol consumption data and the history of alcohol policy in the

U.K.

(Terris, 1998)

Terris further conveyed that he had been

unaware of the critical

commentary surrounding his paper's presentation, as reported in Robin

Room's

(1984) essay. Indeed, he asked us to send him copies of the

literature

we had noted to him -- including Herd's (1992) historical article and

Elinson's

(1967) critical comment published in AJPH before Terris's paper

had yet seen publication itself. "I never saw any of these

articles," wrote Terris, "or if I did see the Elinson [1967] AJPH paper,

I must have paid very little attention to it." He

continued,

"I knew of no controversy or difficulty involved in the publication of

my paper, and clearly I either missed or paid no attention to the fact

that Elinson's critique predated mine" (Terris, 1998).

In sum, Terris's marginality to the

alcohol field and

its epidemiological literature, the one-shot character of his

celebrated

paper, his assumption that the issue had been adequately addressed with

the data and analysis he'd presented, and, finally, his tending to

other

interests in the years that followed had effectively insulated him from

the post-1973 emergence of the U.S. puzzle and the commentary

surrounding

it. Even a passing awareness of the commotion that had greeted

his

1966 presentation of the paper might have prompted Terris to make

occasional

checks on the progress of the case his paper had made -- but even that

element, it seems, was missing from the personal and professional

equation.

Terris, himself, was a member of the regular Public Health

establishment

-- a tenured and distinguished professor in the field and one-time

president

of the American Public Health Association -- and not a regular in the

alcohol

studies collegium, with its annual meeting, invisible college, and

intrafield

communications. Terris was thus effectively removed from the

field-reminding

role that he might otherwise have played.

Presentational or substantive sources

of overlooking

Terris's (1967) beverage-specific

inference may, of course,

have been subsequently overlooked because it was insufficiently

stressed

in his paper. In fact, however, this was not the case; and, on

the

contrary, the beverage-specific aspect was strongly stressed.

Beverage-specificity

appears first in the three-sentence abstract atop the title -- the

middle

sentence of which reads, "From the evidence the conclusion is offered

that

mortality from cirrhosis is directly related to per capita consumption

of alcohol from wine and spirits" (p. 2076, emphasis

added).

It appears next in the text proper, in the lead-off sentence of the

section

of the paper titled "Alcohol Consumption" and aimed at marshaling the

cross-national

evidence on behalf of the alcohol-cirrhosis connection. Terris

wrote:

Table 12 shows that the

differences in cirrhosis

mortality in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom are

associated

with differences in the apparent consumption of alcohol from

spirits

and wine. No such association exists for beer; the

apparent

consumption of alcohol from beer is similar in the three

countries.

(Terris, 1967, pp. 2083-2084, emphasis added)

It appears in the first sentence of the

section titled, "Prevention,"

where Terris also lauds the U.K. for the wisdom of a tax policy

succeeding

in weaning the nation away from distilled spirits and in the direction

of beer. It appears again in the first paragraph of the paper's

brief

"Summary" section: "The evidence strongly supports the conclusion

that cirrhosis mortality is directly related to per capita consumption

of alcohol from spirits and wine." Finally, the legends to

Terris's

Figure 3, 4, & 5, showing the trend relationships between

consumption

and cirrhosis in the U.S., Canada, and the U.K., all explicate that

"absolute

alcohol from spirits and wine" is depicted. Clearly, obscurity

within

Terris's text was not the overlooking's source.

Other aspects of the paper, however, may

have lessened

its utility, compromised its authority, or otherwise engendered a

dismissive

disposition within the alcohol-epidemiological readership. Three

such substantive aspects may be noted. First, almost three-quarters of

Terris's narrative was devoted to a systematic critique of Lilienfeld

and

Korns's 1950 critique of alcohol's place in the epidemiology of

cirrhosis,

which paper was in turn framed around a critique of Jolliffe and

Jellinek's

1942 assessment of cirrhosis's relationship to alcohol or

alcoholism.

This "backward-looking" focus, in turn, may have lent a sense of

datedness

to Terris's text. By the time the alcohol-cirrhosis link became

revivified

in alcohol epidemiology – with, say, the publication of Bruun et al.

(1975)

-- Terris's critique of Lilienfeld and Korns' (1950) environmental and

occupational approach may have seemed passe and anachronistic to some

alcohol-epidemiological

readers. Second, Terris had employed the most basic of

statistical

methods (cross-tabulations, Pearson's product-moment correlations, and

visual inspection of trend-lines) in his analysis. The alcohol

epidemiology

field's subsequent tendency toward more complex statistical methods and

statistical valorization may also have lent Terris's analysis an

outdated

quality for some readers. Third, and finally, Terris's historical

framing of his argument may have appeared slightly askew to some

readers

long familiar with the alcohol epidemiology field. Terris's

narrative

suggested that his paper sought in effect to rescue Jolliffe and

Jellinek's

(1942) correct emphasis on alcohol's cirrhogenic responsibility from

the

incorrect and revisionist non-alcohol emphasis of Lilienfeld and Korns'

(1950) subsequent paper. Jolliffe and Jellinek (1942), however,

took

a rather more critical stance toward alcohol's causal responsibility

for

cirrhosis than Terris's paper suggests. Hence, Room (1984), Herd

(1992), and Katcher's (1993) positioned Jolliffe and Jellinek's (1942)

review paper as consistent with the post-Repeal era's de-emphasis on

alcohol's

causal responsibility for cirrhosis and other bodily illnesses – in

Katcher's

(1993) phrase, there was a "post-Repeal eclipse in knowledge about the

harmful effects of alcohol." Moreover, Jolliffe and Jellinek

(1942)

had focused their attention on alcoholism's (not alcohol's)

relationship to cirrhosis whereas Terris's analysis stressed per capita

consumption's causal relationship. Jolliffe and Jellinek (1942)

had

argued (as Lilienfeld and Korns' also recounted) that cirrhosis was correlated

with alcoholism but not necessarily causally related to it –

once

again, deviating from the path of Terris's paper's rhetorical

trajectory.

How much such factors may have diminished the citation worthiness of

Terris's

paper is of course impossible to gauge, though we suspect such impact

was

minimal at most.

Paradigmatic aspects of Terris's

overlooking

We turn, finally, to sketching a

paradigmatic perspective

on the overlooking of the beverage-specific aspect of Terris's 1967

paper.

Cirrhosis represented a focus of scientific interest in two of the

three

major alcohol-problems paradigms vying for attention and use in the

1970s

-- i.e., in the modern alcoholism paradigm and the alcohol

controls

paradigm though not in the cultural integration paradigm.3

The scientific significance of cirrhosis in the alcoholism and alcohol

controls paradigms differed. In the alcoholism paradigm,

cirrhosis per se harbored relatively little interest save as an

indicator

phenomenon useful for estimating the prevalence of alcoholism – via the

famous and controversial Jellinek Formula (Argeriou, 1974; Roizen and

Milkes,

1980). In the alcohol controls paradigm, on the other

hand,

cirrhosis – and particularly cirrhosis mortality trends -- occupied the

more important position of the paradigm's initial primary scientific explicandum,

i.e., the chief phenomenon to be explained by the paradigm.

Cirrhosis, per se, was not seen as

an important

research focus within the alcoholism paradigm for three main

reasons:

(1) cirrhosis was not seen as caused by either alcohol or alcoholism

(though

it was regarded seen as correlationally associated with alcoholism)

(Jolliffe

and Jellinek, 1942), (2) cirrhosis mortality, in general, and cirrhosis

mortality "with mention of alcoholism," in particular, were not

regarded

as big cause-of-death categories in terms of annual mortality rates,

and

(3) alcoholism itself provided the era's main problem focus. The alcoholism

paradigm's hegemony in the U.S. spilled over into the Canadian

research

establishment in the 1950s and 1960s, a fact broadly indicated by ARF's

original name: the Alcoholism Research Foundation.4

When John Seeley (1960) undertook to write his seminal paper on the

history

of the Canadian alcohol controls paradigm perspective – a

paper

showing a close association between real price and cirrhosis (via real

price's putative impact on consumption) -- he faced the problem of the

relative insignificance accorded cirrhosis, per se, in the

still-dominant alcoholism

paradigm perspective.

In the abstract at least, two main

rhetorical options

were available to Seeley as he composed his paper: (1) he could confine

his discussion to cirrhosis, per se – in effect addressing his analysis

to a relatively insignificant scientific problem in terms of the

prevailing

alcoholism-paradigm sensibility or (2) he could explicitly link

cirrhosis

to the prevalence of alcoholism – in effect "borrowing" the widely

accorded

significance of alcoholism in order to lend his analysis additional

scientific

and policy significance. Seeley (1960) took the first option, a

choice

clearly reflected in the way he framed his introduction:

Any condition that causes death

may well be of

interest to physicians, no matter how relatively rare the

prevalence.

More particularly might they be interested if, simultaneously,

prevalence

were rising while measures, perhaps quite simple, to reduce these death

rates appeared to be available. (Seeley, 1960, p. 1361)

As this text reveals, Seeley finessed the

significance issue

by arguing that though a problem may not be large or pressing in its

own

right, it might nevertheless get larger and moreover a simple

preventive

measure (increased taxation/price) might obviate that prospect.

Several

plausible reasons may have been involved in Seeley's rejection of the

second

option. By 1960, Seeley had already become critical of the

putative

link between cirrhosis mortality and alcoholism's prevalence; indeed,

he

had published in 1959 undoubtedly the deepest and most devastating

critique

of the Jellinek Formula (Seeley, 1959). Moreover, Seeley may already

have

been formulating the conceptual ingredients for his equally critical

and

brilliant assessment of the disease concept of alcoholism (Seeley,

1962),

the conceptual core of the alcoholism paradigm. Seeley

may

also have sought his price-cirrhosis analysis to launch a distinctively

different and new approach to alcohol-problems science, one independent

of the conceptual and policy commitments of the alcoholism paradigm.

Though Seeley mentioned the cirrhosis-alcoholism connection in the

first

page of his text, he did so with well-measured reservation, leaving the

question of the degree of association between cirrhosis mortality and

alcoholism's

prevalence to future research.5 Finally, Seeley may

have

wished simply to confine his analysis and its rhetorical framing to the

objects to which he had paid his scientific attention: cirrhosis

mortality, real price, and per capita alcohol consumption.

Whether or not Seeley actually

contemplated the second

option in composing his paper, this option posed a number of dauntingly

problematic prospects. Whereas Seeley's analysis of real

price,

consumption, and cirrhosis mortality relatively avoided a direct

challenge

to the alcoholism paradigm, the addition of the

cirrhosis-alcoholism

connection to his text would have implied a direct assault on one of

the

key commitments of the disease concept of alcoholism – which concept,

of

course, included a heavy presumption that the alcoholic was very

strongly

wedded to his drinking indeed and therefore hardly a fit candidate for

mere price changes to alter his or her drinking behavior. By

stopping

short of stressing the cirrhosis-alcoholism connection, Seeley in

effect

eschewed a much more difficult and weighty rhetorical task.

Additional problematics attended making

use of the borrowed

significance offered by linking cirrhosis to alcoholism's

prevalence.

The deepest of these ultimately derived from the fact that the two

paradigms, alcohol

controls and alcoholism, took strikingly different

perspectives

on alcohol consumption at both the individual and aggregate

levels.

Fundamental to the alcoholism paradigm's perspective was the

conviction

that society's alcohol-related problems lay with "the alcoholic" and

not

with "alcohol" or "alcohol consumption" per se. Indeed,

the

alcoholism perspective had provided what students of the early history

of American alcohol science regard as an important scientific and

cultural

escape-hatch from the longstanding – but by then very unpopular – focus

of Dry attention on alcohol, per se (Room, 1978; Roizen, 1991,

forthcoming;).

The post-Seeley alcohol controls paradigm perspective, on the

other

hand, positioned alcohol consumption as the key factor from which

sprang

cirrhosis, alcoholism, and (in due course) a still larger gamut of

alcohol-related

problems. The selective borrowing by alcohol controls paradigm

advocates of the alcoholism concept from the alcoholism paradigm

perspective could be expected, therefore, to harbor deep, if

submerged,

cross-paradigm strains or contradictions.

Eventually, however, a number of Seeley's

colleagues at

ARF would lay claim to the cirrhosis-alcoholism connection, thereby

enhancing

the scientific significance of the alcohol controls paradigm's

focus

on cirrhosis. De Lint and Schmidt (1971), for example,

directly

linked the emergent alcohol controls paradigm's focus on

alcohol

consumption to cirrhosis in a paper titled, "Consumption Averages and

Alcoholism

Prevalence." This paper's first paragraph set the conceptual

framework

as follows:

In the epidemiology of alcoholism

two distinct

lines of research are clearly evident. In one series of

investigations

the overall level of alcohol consumption in a population is considered

to be of crucial importance. Accordingly, attention is

focused

on the precise nature of the relationship between consumption

averages

and alcoholism prevalence, as well as on the various socio-cultural

factors that may explain variation in per capica consumption. In

many other epidemiological studies the etiological significance of the

overall level of alcohol consumption in a population is largely

ignored.

(De Lint and Schmidt, 1971, p. 97, emphasis added)

Clearly, per capita alcohol consumption and

alcoholism's

prevalence are directly linked.

In a similar vein, Popham et al. (1978

[1970-1971]) introduced

their essay on "Government Control Measures to Prevent Hazardous

Drinking"

by arguing that cirrhosis mortality was associated with a wide variety

of alcohol-related problems. Numerous previous analyses, they

wrote,

had satisfied them that "despite certain shortcomings, several of the

statistics

could be employed as valid indicators of the magnitude of alcohol

problems

in an area. Most particularly, reported liver cirrhosis mortality

proved to vary in close association with variations in the prevalence

of

alcoholism. (Popham et al., 1978 [1970-1971], p. 240). "This

association

[i.e., between cirrhosis and alcoholism]," the authors continued, "was

assumed by Jellinek in order to develop an alcoholism prevalence

estimation

formula; it has been verified since through case-finding surveys and

other

methods in Ontario and elsewhere" (loc. cit.). Unlike Seeley

(1959,

1960), therefore, Popham et al. (1978 [1970-1971]) elected to

shore-up

rather than criticize or pass over the Jellinek Formula and its

potential

rhetorical benefits for the alcohol controls paradigm.

The rhetorical circumstance thus had the

odd effect of

prompting Popham (1970), an alcohol controls paradigm advocate,

to defend the beleaguered Jellinek Formula fully a decade after that

paradigm

had been effectively demolished by critiques offered in the Quarterly

Journal of Studies on Alcohol by Seeley (1959) and Brenner (1959),

which prompted Jellinek (1959) himself to call for the formula's

retirement

from service. Because the cirrhosis-to-alcoholism link had

rhetorical

value for the alcohol controls paradigm, a reasonably sound

Jellinek

Formula was more useful than a discredited and abandoned one.

Unlike

Seeley (1960), too, Popham et al. (1978 [1970-1971]) braved to throw

their

pro-alcohol controls paradigm argument directly into the teeth

of

some of the alcoholism paradigm's key conceptual commitments. For

example, regarding the specially intractable character of alcoholic

drinking

behavior, Popham et al. (1978 [1970-1971], p. 264) wrote, "...we are

not

aware of any compelling evidence that there is a unique

predisposing

factor or an irreversible change due to chronic intake, which renders

the

individual permanently incapable of controlling his alcohol

consumption."

Gone, in short, was Seeley's (1960) apparent reluctance to

shoulder

the added rhetorical burdens of the cirrhosis-alcoholism link, and in

its

place was a new and vigorous willingness to take these up.

But the 1970s were also a time of troubles

for the alcoholism

paradigm, a circumstance perhaps especially reflected in the

emergence

of a fractious mid-decade controversy over the possibility of

controlled-drinking

among diagnosed alcoholics (Roizen, 1987). The alcoholism

paradigm

perspective's decline in scientific value doubtless also in due course

reduced the value of rhetorical borrowings from its corpus for alcohol

controls paradigm advocates. By 1980, moreover, Bruun (1980,

p. 366) -- in his comment on the significance of Skog's (1980a)

treatment

of lagged effects of consumption change on cirrhosis mortality trends –

had pronounced the Jellinek Formula and its "nebulous logic" as

obsolete

and unnecessary.

The alcohol controls paradigm was

not however thereby

wholly deprived of a link between cirrhosis mortality and a wider orbit

of alcohol-related problems. That linkage, once supplied by the alcoholism

paradigm's Jellinek Formula, could also be supplied by Ledermann's

(1956) single-distribution or log-normal model of popular alcohol

consumption.

Ledermann's model suggested a determinate relationship between mean per

capita total alcohol consumption and the proportion of heavy drinkers

in

the population. The conceptual linkage, in turn, allowed the alcohol

controls paradigm's advocates to in effect substitute "heavy

drinking"

– which via Ledermann's approach was determined by mean per capita

consumption–in

place of "alcoholism" as the mediating concept connecting consumption

with

a wide orbit of alcohol-related problems. Beginning with the

publication

of Bruun et al. (1975), incorporation of the Ledermann's hypothesis

could

be regarded as effectively ridding the alcohol controls paradigm of its

previous reliance on the alcoholism concept and Jellinek's alcoholism

prevalence

estimation formula. Greater paradigmatic integrity and

consistency

could thereby be achieved for the alcohol controls paradigm.

We have outlined the above picture of the

displacing,

liberating, and consistency-achieving picture of the Ledermann model's

service to the alcohol controls paradigm because it suggests a

conceptual

scenario for interpreting the overlooking of Terris's (1967)

beverage-specific

inference in the subsequent epidemiological literature. That

scenario

relies on two aspects of the emergent unfolding paradigmatic

situation:

first, that the Ledermann model could provide the valuable service of

linking

per capita alcohol consumption and a wide array of alcohol-related

problems,

and, second, that the Ledermann model's focus on total per

capita

alcohol consumption may have disinclined alcohol controls paradigm

advocates from beverage-specific lines of investigation because the

Ledermann

model's value to that paradigmatic perspective was substantial, and a

beverage-specific

perspective would vitiate the Ledermann model's authority and

utility.

Therefore, the specifically beverage-specific aspect of Terris's (1967)

analysis may have been regarded as diversionary or even

counterproductive

to the extent that beverage-specific investigations would in effect

undermine

the welcome utility that the Ledermann model was perceived to have

granted

the alcohol controls paradigm. In short, the added value

imported

by the incorporation of the Ledermann model to fill the functional role

once filled by the alcoholism paradigm and the Jellinek Formula

was sufficiently great to alcohol controls paradigm advocates

that

the Ledermann models focus on total per capita consumption was adopted

as part of the conceptual package.6

Conclusion

There are, of course, additional

explanatory possibilities

regarding Terris's overlooked beverage-specific inference. For

one,

the puzzle posed by the disparate trends in cirrhosis mortality and per

capita alcohol consumption after 1973 revealed itself slowly and

remembrance

of Terris's (1967) article may have simply faded apace.

Nevertheless,

this problem in scientific forgetfulness or oversight appears to us to

harbor at least a few intriguing implications and lessons. As we

saw, the historical and utilitarian significance of Terris's celebrated

1967 paper may have been quite different. Despite the paper's

historical

significance in subsequent accounts by Room, Herd, and Katcher,

Terris's

marginality to the unfolding story of the epidemiological investigation

of the link between alcohol consumption and cirrhosis mortality may

have

been suggested in both (1) Terris partial garbling of the relationship

between his own paper's thesis and Jolliffe and Jellinek's (1942)

argument

and in (2) Terris's subsequent loss of interest in epidemiological

research

on the alcohol-cirrhosis link. John Seeley may or may not have

contemplated

the two options we laid out in constructing the introduction to his

1960

paper. Whether or not he did, our analysis suggests that two

quite

different dispositions to the scientific significance of cirrhosis

mortality

trend studies were implied in his choice of a modest direction.

Conflict

and the changing relationship between the alcohol controls and modern

alcoholism paradigms, we have argued, merit a significant place in

the interpretation of Terris's overlooking. All or which suggests

the value of keeping a keen eye on the history and sociology of science

aspects of alcohol epidemiological studies through time.

Notes

1This tendency

was by no means

confined to

the U.S. alone. For example, French students of the relationship,

Masse et al. (1976, p. 41), wrote: "It is interesting to note the

development of concepts regarding cirrhosis of alcoholic origin.

At the end of the Second World War the shortage of proteins in many

countries

drew the attention of research workers and physicians to the

nutritional

origin of a number of diseases. Some experimental studies

convinced

medical opinion that there was an important link between animal protein

deficiency and cirrhosis. In some countries the importance of

alcohol

in the origin of cirrhosis of the liver was actually denied; however,

medical

opinion has hanged during the last 15 years and the role of alcohol has

gradually won fresh recognition."

2Here, as

elsewhere in the

alcohol-cirrhosis

epidemiological literature, Lelbach's (1974, 1976) impressive and

influential clinical

reviews may have acted as roadblocks to investigation of

beverage-specific

aspects the alcohol-cirrhosis relationship at the epidemiological

level.

3The 1970s saw

the heyday of

paradigm wars

in alcohol epidemiology and alcohol studies more generally. The modern

alcoholism paradigm had been largely responsible for ushering

alcohol

science into existence in the U.S., and -- though it was already

suffering

a variety of problematics -- still enjoyed considerable dominance in

the

field. In the early 1970s, the cultural integration paradigm

experienced a sudden limelight in the U.S. via its embracement by

Morris

Chafetz, the first director of the still-new U.S. National Institute on

Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) (see Room, 1991, p. 320 et

seq.).

Finnish alcohol researchers were simultaneously recoiling from what

seemed

a failed experiment in adopting the liberalizing dictates of the cultural

integration paradigm (see Beauchamp, 1981). Lastly, the alcohol

controls paradigm was taking shape and attracting increasing

interest,

especially at Ontario's Addiction Research Foundation (ARF), becoming

associated

with a distinctively "Canadian" viewpoint and research preoccupation

(see

Room, 1996). The names Schmidt, Smart, Popham, Seeley, de Lint --

all out of ARF -- became familiar in the alcohol controls paradigm

sub-literature, though the paradigm also had strong ties to France and

to Scandinavian alcohol research and policy.

4Smart (1998, p.

11) recently

recalled of his

first encounter with Kettil Bruun (late 1950s or early 1960s?): "Kettil

thought our [i.e., ARF's] research group was ‘too Jellinek-centred' and

we paid too much attention to his ideas. He was probably right."

5Seeley (1960, p.

1361) wrote

of the cirrhosis-alcoholism-prevalence

link: "Some forms of liver cirrhosis, and more particularly some

cirrhosis of sufficient severity to be a cause of death, has long been

widely spoken of as a ‘complication of alcoholism' [incidentally,

citing

Jolliffe and Jellinek, 1942]. Indeed so close has the relation

been

held to be that liver cirrhosis death rates have provided the basis

upon

which nearly all alcoholism prevalence rates have been estimated even

though

it is not known what proportion, within very wide limits, of such

deaths

are due to or associated with alcoholism [three citations, including

Seeley,

1959].

"Given the fact, however, of

a strong

association between

liver cirrhosis deaths and ‘alcoholism prevalence', we might well ask

how

close the association is between the death rate from cirrhosis and the

consumption of beverage alcohol.

"If, moreover, that

association should

prove to be close

and positive, then an interest in economics or public health will

prompt

us to enquire further as to the dependence of alcohol consumption on

the

price of alcohol. It is into these two aspects that this paper

is,

more narrowly, to enquire."

6Our suggested

picture of the

Ledermann model's

significance in relation to the liberation of the alcohol controls

paradigm

from the alcoholism paradigm may shed light upon and draw some

support

from a related history-of-alcohol-science puzzle. The Ledermann

model,

per se, has been the subject of numerous and in some cases withering

criticism

from both outside and inside the alcohol controls policy camp

(Miller

and Agnew, 1974; Parker and Harman, 1974; Duffy, 1980, 1982, 1986;

Duffy

and Cohen, 1978) – even from such leading pro-controls figures as

Ole-Jorgen

Skog (1980b) and Robin Room (1978 [1970-1971] pp. 276-280).

Such criticism suggests, of course, that the Ledermann model harbors its

own considerable complement of pitfalls and problematics. But

the Ledermann element as incorporated into the larger alcohol

controls

paradigm perspective has shown remarkable viability and gained a

seemingly

integral role in the pro-alcohol controls paradigm rhetorical

armamentarium

– from Bruun et al. (1975) to Edwards et al. (1994) and the World

Health

Organization's working group's summary statement (Rehm et al.,

1996).

The Ledermann model's remarkable endurance within the story of the alcohol

controls paradigm, despite its record of important criticisms, may

afford yet another indicator that the function served by its proffered

linkage between total per capita consumption and the proportion of

heavy

drinkers is too valuable to allow the Ledermann hypothesis to be

allowed

to fall out of the control paradigm's structure. The

mindset

that perceives this high utility for the Ledermann model, we suggest,

has

its origins in the previous reliance on the alcoholism paradigm

and the Jellinek Formula as the significance-granting link between

cirrhosis

and a greater orbit of alcohol-related problems. Hence, and by

extension,

the remarkable endurance of the Ledermann model within this

paradigmatic

camp may further evidence the importance of its preoccupation with

total

per capita alcohol consumption and therefore the relative indifference

to the beverage-specific aspect of Terris's (1967) analysis.

References

Argeriou, M., "The Jellinek Estimation

Formula Revisited," Quarterly

Journal of Studies on Alcohol 35:1053-1057, 1974.

Battig, K., "Ausmass und Ursachen des

Alkoholismus," Zeitschrift

fur Praventivmedizin 9:133-142, 1964 (cited in Schmidt, 1975).

Beauchamp, D.E., "The Paradox of Alcohol

Policy: The Case

of the 1969 Alcohol Act in Finland," pp. 225-254 in Moore, M., and

Gerstein,

D. (eds.), Alcohol and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow of

Prohibition,

Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1981.

Brenner, B. Estimating the prevalence of

alcoholism; toward

a modification of the Jellinek formula. Quarterly Journal of

Studies

on Alcohol 20: 255-260, 1959.

Bruun, K., Edwards, G., Lumio, M., Makela,

K., Pan, L.,

Popham, P., Room, R., Schmidt, W., Skog, O.-J., Sulkunen, P., and

Osterberg,

E., Alcohol Control Policies in Public Health Perspective,

Helsinki:

The Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, 25, 1975.

Cook, P.J., "The effect of liquor taxes on

drinking, cirrhosis,

and auto accidents," pp. 255-285 in Moore, M., and Gerstein, D.(eds.), Alcohol

and Public Policy: Beyond the Shadow of Prohibition, Washington,

DC:

National Academy Press, 1981.

De Lint, J., "Critical examination of data

Bearing on

the type of alcoholic beverage consumed in relation to health and other

effects," British Journal of Addiction 72:189-197, 1977.

De Lint, J., and Schmidt, W., "Consumption

averages and

alcoholism prevalence: a brief review of epidemiological

investigations," British

Journal of Addiction 66:97-107, 1971.

Duffy, J.C., "The association between per

capita consumption

of alcohol and the proportion of excessive consumers – a reply to

Skog," British

Journal of Addiction 75:147-151, 1980.

Duffy, J.C., "Fallacy of the distribution

of alcohol consumption," Psychological

Reports 50:125-126, 1982.

Duffy, J.C., "The distribution of alcohol

consumption–30

years on," British Journal of Addiction 81:735-741, 1986.

Duffy, J.C., and Cohen, G.R., "Total

alcohol consumption

and excessive drinking," British Journal of Addiction

73:259-264,

1978.

Edwards, G., Anderson, P., Babor, T.F.,

Casswell, S.,

Ferrence, R., Giesbrecht, N. et al., Alcohol Policy and the Public

Good,

Oxford, New York, Tokyo: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Elinson, J., "Epidemiological studies and

control programs

in alcoholism: Discussion," American Journal of Public Health

57:991-996,

1967.

Grant, B.F., Noble, J., and Malin, H.,

"Decline in liver

cirrhosis mortality and components of change: United States,

1973-1983," Alcohol

Health & Research World 10:66-69, 1986.

Gruenewald, P.J., and Ponicki, W.R., "The

relationship

of alcohol sales to cirrhosis mortality," Journal of Studies on

Alcohol

56:635-641, 1995.

Herd, D., "Ideology, history and changing

models of liver

cirrhosis epidemiology," British Journal of Addiction

87:1113-1126,

1992.

Jellinek, E.M., "Estimating the prevalence

of alcoholism:

modified values in the Jellinek Formula and an alternative approach," Quarterly

Journal of Studies on Alcohol 20: 261-269, 1959.

Jolliffe, N., and Jellinek, E.M.,

"Cirrhosis of the liver,"

in Jellinek, E.M. (ed.), Alcohol Addiction and Chronic Alcoholism,

ch. VI, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1942.

Katcher, B., "The Post-Repeal Eclipse in

Knowledge About

the Harmful Effects of Alcohol," Addiction 88:729-744,

1993.

Leevy, C.M. in: Engel, A. and Larsson, T.

(eds.), Alcoholic

Cirrhosis and other Toxic Hepatopathias, Stockholm: Skandia, 1970

(cited

as "Leavy" in Smith and Burvill [1985]).

Ledermann, S., Alcool, Alcoolisme,

Alcoolisation,

Vol. 1, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1956.

Lelbach, W.K., "Organic Pathology Related

to Volume and

Pattern of Alcohol Use," in Gibbens, R.S. et al. (eds.), Research

Advances

in Alcohol and Drug Problems, New York: Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1974

(cited in Schmidt [1975] and Smith and Burvill [1985]).

Lelbach, W.K., in Popper, H., and

Schaffner, F. (eds.), Progress

in Liver Diseases, Vol. 5, New York: Grune and Stratton, 1976

(cited

in Smith and Burvill, 1985).

Lieber, C.S., Medical Disorders of

Alcoholism,

Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1982 (cited in Smith and Burvill [1985]).

Lilienfeld, A.M. and Korns, R.F., "Some

epidemiological

aspects of cirrhosis of the liver: a study of mortality statistics," American

Journal of Hygiene 52:65-81, 1950.

Longnecker, M.P., Wolz, M., and Parker,

D.A., "Ethnicity,

Distilled Spirits Consumption and Mortality in Pennsylvania," Journal

of Studies on Alcohol 42:791-796, 1981.

Makela, K. "Reports from Research

Centers–9: The Finnish

Foundation for Alcohol Studies and the Social Research Institute of

Alcohol

Studies," British Journal of Addiction 83:141-148, 1988.

Mann, R.E., Smart, R.G., Anglin, L., and

Rush, B.R., "Are

decreases in liver cirrhosis rates a result of increased treatment for

alcoholism?" British Journal of Addiction 83:683-688, 1988.

Mann, R.E., Smart, R.G., Anglin, L., and

Adlaf, E.M.,

"Reductions in cirrhosis deaths in the United States: associations with

per capita consumption and AA membership," Journal of Studies on

Alcohol 52:361-365,

1991.

Masse, L., Juillan, J.M., and Chisloup,

A., "Trends in

mortality from cirrhosis of the liver, 1950-1971" World Health

Statistics

Report 29:40-67, 1976.

Miller, G.H, and Agnew, N., "The Ledermann

model of alcohol

consumption," Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol

35:877-898,

1974.

Moeschlin, S., and Righetti, P., "Wine and

the Liver,"

pp. 301-311 in Engel, A. and Larsson, T. (eds.), Alcoholic

Cirrhosis

and other Toxic Hepatopathias, Stockholm: Skandia, 1970 (cited in

Smith

and Burvill (1985).

Moore, M., and Gerstein, D. (eds.), Alcohol

and Public

Policy: Beyond the Shadow of Prohibition, Washington, DC: National

Academy Press, 1981.

Parker, D.A., and Harmon, M.S., "The

distribution of consumption

model of prevention of alcohol problems: a critical assessment," Journal

of Studies on Alcohol 39:377-399, 1978.

Peele, S., "R. Brinkley Smithers: The

Financier of the

Modern Alcoholism Movement," World Wide Web page at

http://www.peele.net/lib/smithers.html.

Popham, R.E., "Indirect Methods of

Alcoholism Prevalence

Estimation: A Critical Evaluation," pp. 294-306 in Popham, R.E. (ed.), Alcohol

and Alcoholism, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1970.

Popham, R.E., Schmidt, W., and de Lint,

J., "Government

Control Measures to Prevent Hazardous Drinking," pp. 239-266 in Ewing,

J.A., and Rouse, B.A. (eds.), Drinking: Alcohol in American

Society–Issues

and Current Research, Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1978 [1970-1971]

(probably

written in 1970-1971).

Rehm, J., Room, R., and Anderson, P.,

"WHO working

group on population levels of alcohol consumption," Addiction

91:275-283,

1996 (see Addiction 91:896, 1996, for amended authorship).

Roizen, R., "How Does the Nation's

'Alcohol Problem' Change

from Era to Era? Stalking the Social Logic of Problem-Definition

Transformations Since Repeal," in Sarah Tracy and Caroline Acker

(eds.), Altering

the American Consciousness: Essays on the History of Alcohol and Drug

Use

in the United States, 1800-1997, University of Massachusetts Press

(originally presented at the conference on Historical Perspectives on

Alcohol

and Drug Use in American Society, 1800-1997, sponsored by the Francis

Clark

Wood Institute for the History of Medicine of the College of Physicians

of Philadelphia, 9-11 May 1997), forthcoming.

Roizen, R., The American Discovery of

Alcoholism, 1933-1939,

Ph.D. diss., sociology, University of California, Berkeley, 1991.

Roizen, R., "The Great Controlled-Drinking

Controversy,"

pp. 245-279 in Galanter, M. (ed.), Recent Developments in Alcoholism,

Vol. 5, New York: Plenum, 1987.

Roizen, R., Kerr, W.C., and Fillmore,

K.M., "Cirrhosis

mortality and per capita consumption of distilled spirits, United

States, 1949-94: Trend analysis," British Medical Journal

319:666-670,

1999.

Roizen, R., and Milkes, J., "The Strange

Case of the Jellinek

Formula's Sex Ratio," Journal of Studies on Alcohol 41:682-692,

1980.

Room, R., 1978 [1970-1971], "Evaluating

the effects of

drinking laws on drinking, pp. 267-289, 414-419 in Ewing, J.A., and

Rouse,

B.A. (eds.), Drinking: Alcohol in American Society–Issues and

Current

Research, Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1978 (written in 1970-1971, see

Room

[1984, p. 315, ref. no. 77]).

Room, R., Governing Images of Alcohol

and Drug Problems:

The Structure, Sources and Sequels of Conceptualization of Intractable

Problems, Ph.D. diss., sociology, University of California,

Berkeley,

1978.

Room, R., "Alcohol control and public

health," Annual

Review of Public Health 5:293-317, 1984.

Room, R., "Social Science Research and

Alcohol Policy

Making," pp. 315-339 in Roman, P.M. (ed.), Alcohol: The Development

of Sociological Perspectives on Use and Abuse, New Brunswick, NJ:

Rutgers

Center of Alcohol Studies, 1991.

Room, R, "Introduction," pp. xi -xiv

in Smart,

R.G. and Ogborne, A.C., Northern Spirits: A Social History of

Alcohol

in Canada, 2nd ed., Toronto: ARF, 1996.

Schmidt, D.N., "Apparent risk factors for

chronic and

acute pancreatitis in Stockholm County: spirits but not wine and beer,"

International

Journal of Pancreatitis 8:45-50, 1991.

Schmidt, W., "Agreement, Disagreement in

Experimental,

Clinical and Epidemiological Evidence on the Etiology of alcoholic

Liver

Cirrhosis: A Comment," pp. 19-30 in Khanna, J.M. et al. (eds.), Alcoholic

Liver Pathology, Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation, 1975.

Schmidt, W., "Cirrhosis and alcohol

consumption: an epidemiological

perspective," pp. 15-47 in Edwards, G., and Grant, M. (eds.), Alcoholism:

New Knowledge and New Responses, Baltimore, London, Tokyo:

University

Park Press, 1977a.

Schmidt, W., "The epidemiology of

cirrhosis of the liver:

a statistical analysis of mortality data with special reference to

Canada,"

pp. 1-26 in Fisher, M.M. and Rankin, J.G. (eds.), Alcohol and the

Liver,

New York and London: Plenum Press, 1977b.

Schmidt, W., and Bronetto, J., "Death from

liver cirrhosis

and specific alcoholic beverage consumption: an ecological study," American

Journal of Public Health 52:1473-1482, 1962.

Skog, O.-J., "Liver cirrhosis

epidemiology: some methodological

problems," British Journal of Addiction 75:227-243, 1980a.

Skog, O.-J., "Is alcohol consumption

lognormally distributed?" British

Journal of Addiction 75:169-173, 1980b.

Seeley, J.R., "Estimating the prevalence

of alcoholism:

a critical analysis of the Jellinek Formula," Quarterly Journal of

Studies

on Alcohol 20:245-254, 1959.

Seeley, J.R., "Death by liver cirrhosis

and the price

of beverage alcohol," Canadian Medical Association Journal 83:1361-1366,

1960.

Seeley, J.R., "Alcoholism is a disease:

implications for

social policy," pp. 586-593 in Pittman, D.J., and Snyder, C.R. (eds.), Society,

Culture, and Drinking Patterns, Carbondale and Edwardsville:

Southern

Illinois University Press (and London and Amsterdam: Feffer &

Simons,

Inc.), 1962.

Selzer, M.I., Vinokur, A., and Wilson,

T.D., "A psychosocial

comparison of drunken drivers and alcoholics," Journal of Studies

on

Alcohol 38:1294-1312, 1977.

Smart, R.G., "The effect of licencing

restrictions during

1914-1918 on drunkenness and liver cirrhosis deaths in Britain," British

Journal of Addiction 69:109-121, 1974.

Smart, R.G., "International Review Series:

Alcohol and

Alcohol Problems Research: 4. Canada," British Journal of Addiction

80:255-263, 1985.

Smart, R.G., "Journal Interview–41:

Conversation with

Reg Smart," Addiction 93:9-15, 1998.

Smart, R.G., and Ogborne, A., Northern

Spirits: Drinking

in Canada Then and Now, Toronto: Addiction Research Foundation,

1986.

Smith, D.I., and Burvill, P.W.,

"Epidemiology of liver

cirrhosis morbidity and mortality in Western Australia, 1971-82:

Some preliminary findings," Drug and Alcohol Dependence,

15,

pp. 35-45, 1985.

Star, S.L., and Griesemer, J.R.,

"Institutional Ecology,

'Translations' and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in

Berkeley's

Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-1939," Social Studies of Science

19:387-420, 1989.

Terris, M., "Epidemiology of cirrhosis of

the liver: national

mortality data," American Journal of Public Health

57:2076-2088,

1967.

Terris, M., personal communication (email,

Thu, 8 Jan

1998 13:40:45 [EST]), 1998.

Tuyns, A.J., Esteve, J., and Pequignot,

G., "Ethanol is

Cirrhogenic, Whatever the Beverage," British Journal of Addiction

79:389-393, 1984.

Wallgren, "Alcoholism and alcohol

consumption," Alkoholpolitik

23:177-179, 1960 (cited in Schmidt, 1975). |